#2 in a series of posts about Capayque, Bolivia, and about theStillwater, Oklahoma Methodist mission group that provides healthcare to Capayque’s residents.

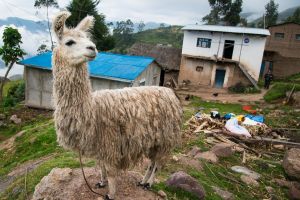

A dirt road passes through Capayque, Bolivia. It’s passable most of the year – except in the rainy season when parts of it are often washed out. A truck comes through town once a week to buy or deliver goods, and a bus comes through a few times a week. Every Monday, the school teachers arrive from La Paz in a car; they sleep at the school, and on Friday they take the car back to the City. Nobody in town owns a car, though I spotted two motorcycles (which may or may not have been operable). Capayque’s only traffic jams are when small herds of sheep (or a handful of cows, or a llama, or a group of small pigs) clog the walking trails through town.

There aren’t any stores in town. There’s a surprisingly big school, an abandoned Catholic church building, a tiny Methodist church and the health clinics (the old one and new one). Other than that, all the buildings are homes. I asked a couple of local people if the animals had any sort of barn or stable to get in out of the weather, and they just laughed at that idea.

Most of the houses are made of mud and stone, and consist of just one or two rooms. Most floors are of dirt. They don’t have bathrooms or running water. In a climate where nighttime temperatures usually dip into the 30s year-round, homes are heated (if at all) with small fires burning in chimney-less rooms that seep smoke out doorways or gaps in the thatched roofs. They’ve had electricity in the village for a decade or so, but few people seem to have any sort of electric fixtures or appliances other than just light bulbs. There don’t seem to be any refrigerators. Chickens wander in and out, and pigs and sheep roam yards and courtyards and usually sleep just a few feet away from their owners.

There seems to be trash all over town — they don’t seem to have much of a grip on disposing of things that are not biodegradable. There are tiny canals running through town with water from spring-fed streams. Some run under the town outhouse (baño) and some are used for clothes washing and drinking, so I can only assume the locals keep track of which is which.

The people survive largely on subsistence farming, so every bit of open space is a small farm/garden, usually growing corn or some form of potato-like vegetables. People spend a surprising amount of time throwing rocks at stray pigs to get them out of the corn patches.

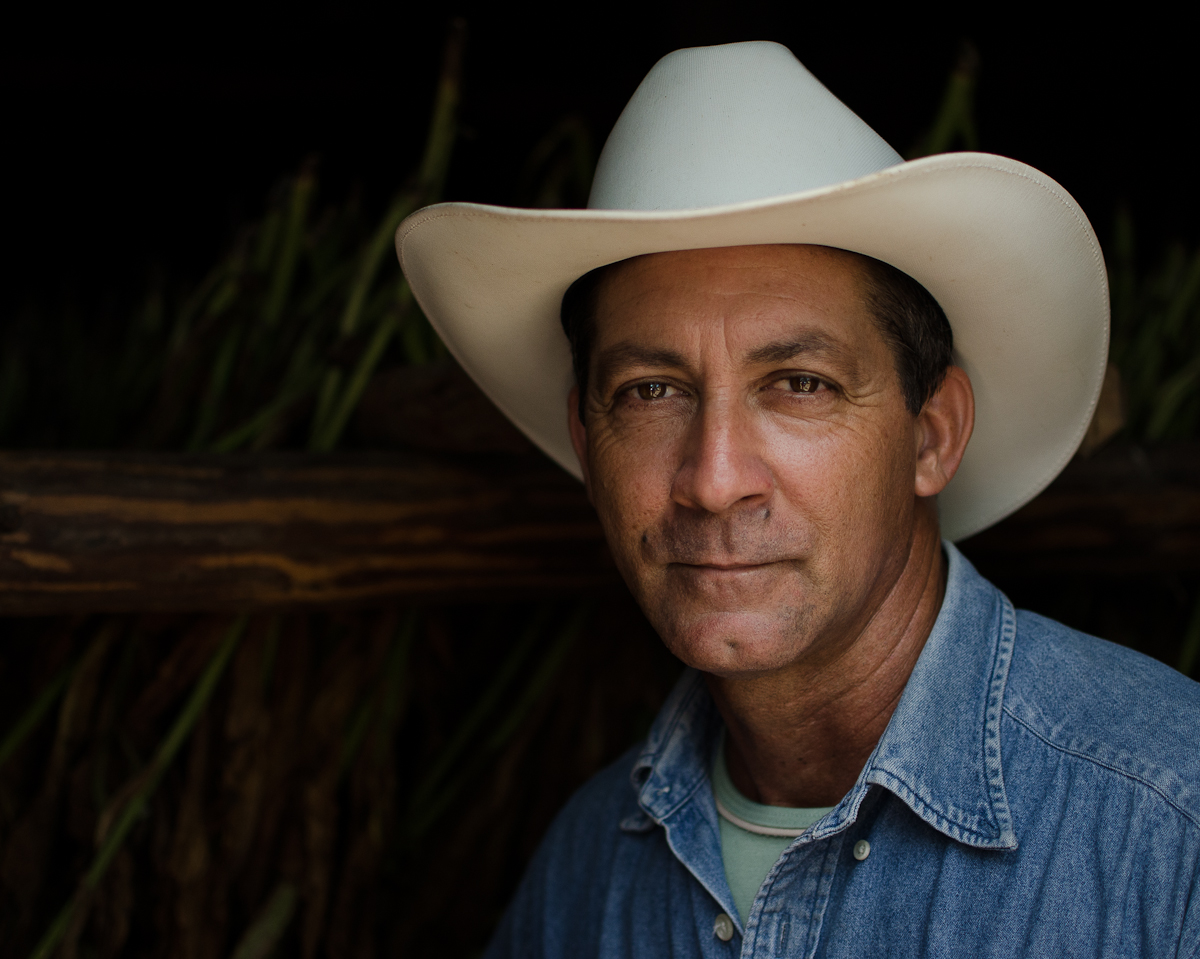

That tiny guy (“Estaban”) is a town’s mayor (or something like that). These digs are probably the nicest house in town.

It’s easy to think of this as “poverty,” but that doesn’t really capture the reality of the situation. More than “poor”, their life is primitive. Except for the kids’ and men’s clothing that have somehow found their way to the villages front the rest of the world, their way of life isn’t much changed or advanced from what it must have been a few hundred years ago. They’re probably as content as people were in the same hillside settlements in the 1400s. The distinction may not matter much, but it’s not so much just a matter of bringing them out of poverty as it is bringing them into the 21st century.