NOTE to South Dakota Folks: CLICK HERE for full set of pics.

Late spring is “branding” season in South Dakota. A local rancher who caught a ride with us to one of the calf branding events called them “celebrations.” The cold winter is over and the year’s crop of calves are a couple of months old and in need of vaccines, brands, and more. The whole community works together almost daily, with all the local ranch families taking turns helping one another. It’s both hard, serious work and social event. Notice in the pictures how often people are smiling.

The fire, ropes, needles and knives look harsh to the uninitiated – and I surely wouldn’t want to be one of the calves. But the health of the cattle is a major purpose of the process. A veterinarian was on site at all times. Every one of the hundreds of calves I saw hopped up and scurried spryly back to its mom as soon as its short ordeal was done.

Emily Linn (right) takes a turn wrestling the front end of a calf during a branding on the Trask’s Spanish Five Ranch.

= = = = = = =

Here’s how the branding process works: The cattle – usually a few hundred pairs (mother and calf) at a time – have been gathered in advance into a single section of pasture. On the morning of the branding, the first hour or two is spent herding them all into a set of pens. Next, the cows are separated from the calves, generally by horsemen urging the adult cows one by one through a gate while a handful of sorters (on foot) push the calves in a different direction. Most of the attention will be on the calves, but the cows may also be sent through separate chutes to get vaccines or other treatments. Batches of 150 or so calves go into a medium sized roping pen adjacent to the branding area – which is set up at the edge of the big pasture.

Three or four mounted ropers go in and out of the calf pen, roping calves by their hind legs and then dragging them out one at a time. Pairs of “wrestlers” (mostly teenagers and younger men) take each calf. One grabs the roped rear legs; the other grabs the tail and shifts quickly to the head. With a swift and skillful yank, they flip the calf onto its side, hold it down legs splayed, and release the rope so the roper can go get another.

Now things really start to happen: people converge on the calf like a pit crew on an Indy car. Two give shots containing multiple vaccines. Others apply treatments for worms, flies and ticks. Another person walks up to crop an ear. If the calf is male, someone with a sharp knife deftly castrates it – an operation that takes about 20 seconds and produces surprisingly little blood. Preschool-aged kids follow the castrators, carrying the self-explanatory “nut buckets.” An antiseptic foam is sprayed on the incision site. Depending on the breed, the calf may be de-horned (by burning the budding nubs of horn using small irons similar to the branding irons). And of course, there’s the brand itself: just an old-fashioned piece of red-hot metal that burns the hair and scars the skin. Between calves, most of the crowd have a beer or two from the cooler – which is usually in a pickup bed next to the laden nut buckets.

= = = = = = =

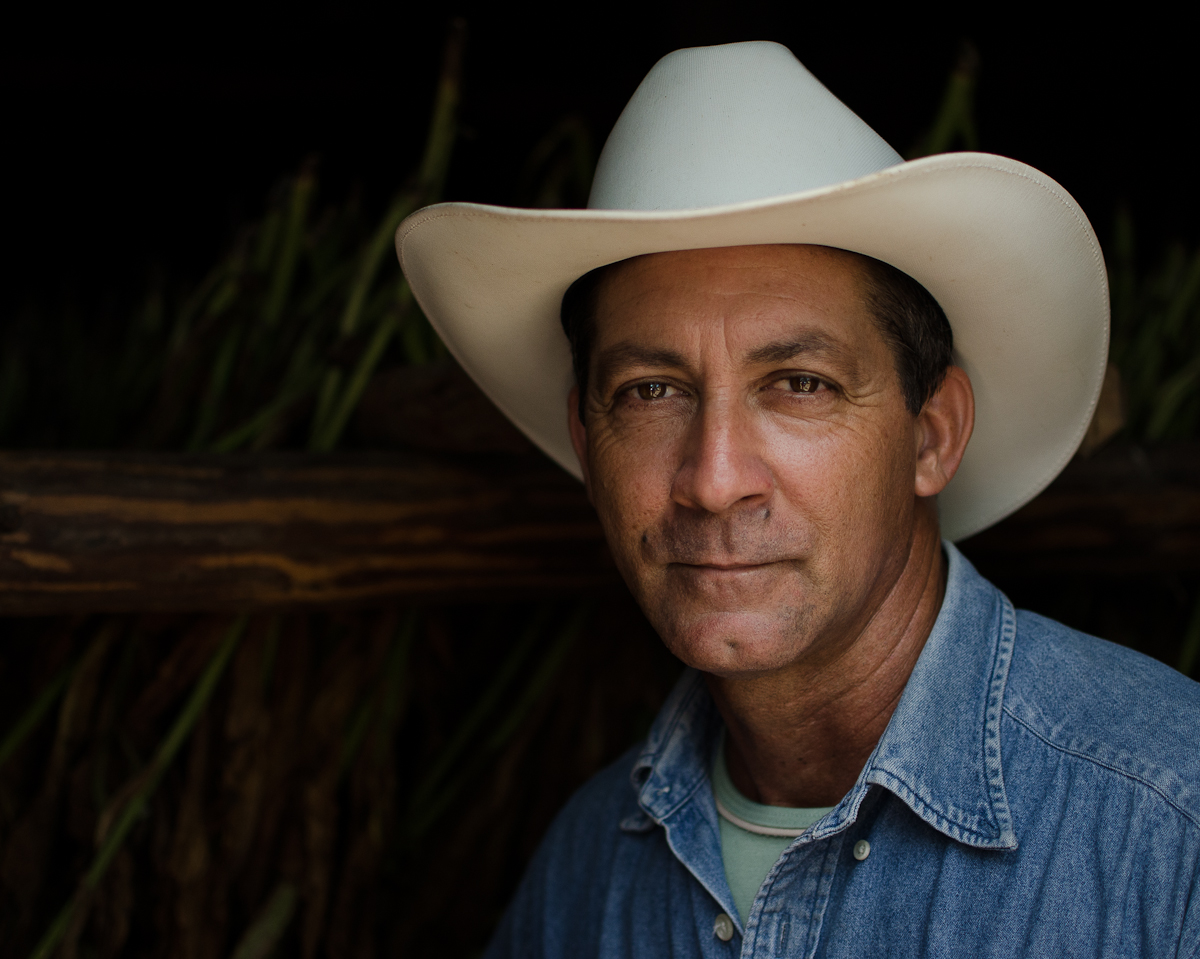

Tom Trask owns around 20,000 acres next to the Cheyenne River east of Rapid City. He and his sons lease several thousand more, for a total of nearly 50 square miles of land. His brother Pat’s ranch is just to the north; his cousin Todd’s place is just to the south. Tom got much of his land from his dad, whose U.S. Army uniform is hung proudly in Tom’s home.

Mark Trask (My apologies to his brother, Mick, and sister Tomilyn, for whom I failed to get good portraits).

If you imagine life on a rural ranch as serene or simple, you should spend a few days with the Trasks. The most striking aspect of my visit was the remarkable array of skills and knowledge required to run a huge ranch like this. They can do an emergency bovine C-section, battle weevils on their hay crop, raise bees to pollenate their alfalfa, train horses for roping, milk cows, build their own houses, weld broken tractor parts back together, recommend the perfect ammo for prairie dog eradication, and drive a pickup through a muddy field without getting stuck. It should tell you something that the one “hired hand” on Tom Trask’s cattle ranch has two college degrees: one in animal (livestock) science; the other in “range” (grazing land) science. They dig 75 million year-old fossils from the creek for extra money. They host paid deer hunts in the fall, and can butcher the venison onsite and do the taxidermy work to mount the trophy.

South Dakota winters are biting cold, the summers are scorching, and blistering spring winds don’t allow much relief in between. The work is hard and the hours are long. Around huge animals and farm machinery, the risks of accidents and injuries are a routine part of life. I overheard one conversation about which kind of tractor would be most easily operated by a young woman with a devastating farm injury that left her with very limited use of her legs. These folks are tough and resilient.

The county sheriff’s office is about an hour and a half away in Sturgis. As in other areas of their lives, the folks here view it as their responsibility to take care of themselves and of their own families, and they’re ready to do so. There are a lot of guns, and people know how to handle them. They say they have very little crime out here. {Note: They’re right. South Dakota’s homicide rate ranks #44 among states; its gun ownership rate ranks #4.}

The folks here are hardworking, loyal, patriotic, and proud – and I think they’d consider those descriptions to be the highest of compliments. In the last few years, I’ve been on six continents and met fascinating people in exotic cultures, but the lives and lifestyles in a down-home and close-to-home place like South Dakota are every bit as interesting and in many ways probably far more relevant for other Americans to appreciate and understand. These folks will vote in the same elections and will have to live by most of the same laws as people from New York City and Washington D.C., and yet each group often has only a faint caricatured picture of one another’s worlds.

My dad and I were in South Dakota in late May and early June. The weather cycled between rainy, chilly, windy, and hot. We stayed in a modest small-town Best Western, and the local Subway and Dairy Queen were the best restaurants in town. Yet it was one of my favorite trips ever. Getting to know the Trasks was a real treat.

* * * * *

A multigenerational “pit crew” descends on a calf (under there somewhere) as Rob Powell pulls the Spanish Five branding iron from the fire. That’s Mick Trask in the camo cap, holding down the head.

Calf roping is an equal-opportunity and co-ed endeavor. Kelly Anders seemed to be one of the best ropers in the county.

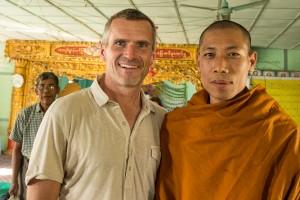

That’s my dad below (green hat) with Todd Trask. He met Todd and Tom 20+ years ago when they were all hanging out together in the mountains of southern Colorado. That’s me (orange vest) with my calf-wrestling buddy/instructor Matthew, who works up at Pat Trask’s ranch. (I didn’t catch the name of the photo-bomber). Matthew taught me how NOT to get kicked in the face by a calf as you restrain its rear legs. It’s harder than you might think. Actually — restraining a 150-pound calf while it’s being castrated is probably exactly as difficult and awkward as it sounds.

CLICK HERE FOR MORE SOUTH DAKOTA 2016 BRANDING WEEK IMAGES